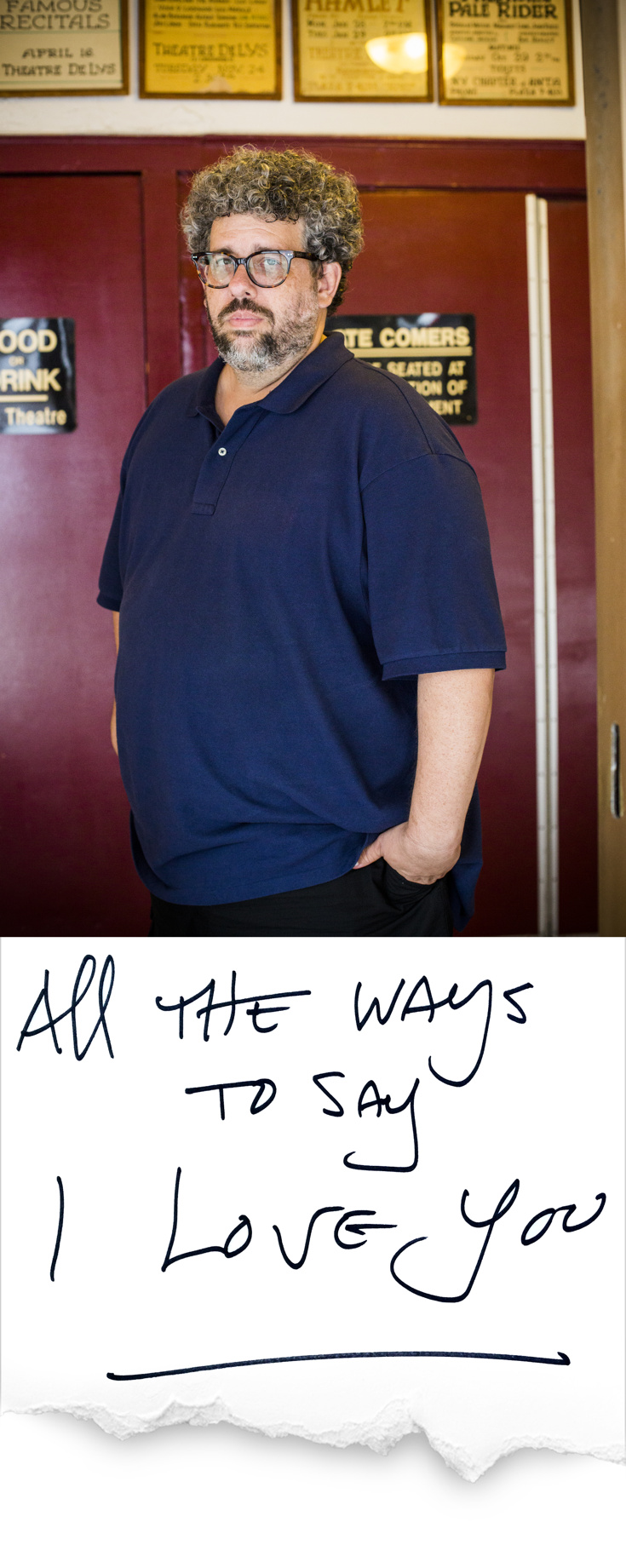

All the Ways to Say I Love You Scribe Neil LaBute on the Secret to Being Prolific & How His Characters Are Alike

(Photo: Caitlin McNaney)

Neil LaBute, known for his daring, often controversial plays, is getting ready to premiere his 10th full-length work at MCC Theater, where he is the playwright-in-residence. The new piece, titled All the Ways to Say I Love You, is a monologue starring two-time Tony winner and Broadway.com Audience Choice Award winner Judith Light. LaBute’s plays include bash: latter-day plays, The Shape of Things, The Mercy Seat, The Distance From Here, Autobahn, Fat Pig, Some Girl(s), This Is How It Goes, Wrecks, Filthy Talk for Troubled Times, In a Dark Dark House, Reasons to Be Pretty and The Break of Noon. His films include In the Company of Men, Your Friends & Neighbors, Possession, The Shape of Things (adapted from his play) and more. LaBute is affable and thoughtful. He met Broadway.com at the Lucille Lortel Theatre, where All the Ways to Say I Love You opens on September 28 to chat about his process, his inspiration and the greatest misconceptions about him.

What inspired All the Ways to Say I Love You?

I like the monologue form and breaking the fourth wall—talking directly or indirectly to the audience. I think that's a great and unique technique to the theater. About 10 years ago, I'd written a solo piece [Wrecks] for a male of a certain age. Ed Harris did it, and I directed it a few times. It was about a marriage, and at the time, I thought I would do [a monologue] from the wife's point of view. I never did, but I thought it would be interesting to do one for a woman. One of my earlier plays, bash, had been based on Greek plays and Wrecks was as well, so I wanted to do something in that vein and Phedre came to mind. What also specifically spun me toward this was I was asked a few years ago to do a modern fairy tale for a collection [My Mother She Killed Me, My Father He Ate Me: Forty New Fairy Tales]. I did Rumplestiltskin, and I wrote it from the point of view of a different character. When it came to the idea of doing this Phedre thing, I thought the story would be interesting if I told it from another person’s point of view. So that was the other thing that led me toward creating this.

How do you collect ideas? Do you keep notebooks? Articles? Images?

A bit of all those things. I’m somewhere between someone who is fastidious like Proust and Francis Bacon. If you've ever seen his studio, it’s a touch messier. Somewhere in there lies my process. I don't take a lot from other people's lives or my life. I'll get an idea and just hold on to it and roll it around in my head for a long time. I do scratch things down in the corners of books and notebooks. There isn't that Moleskine in my pocket all the time, which is probably dumb for someone who does this for a living. For me, if the idea is good enough then it stays with me. If I can't shake it, then I know it's a good one. If you forget it the next morning, it couldn't have been that great.

Where do you generally write?

I've written everywhere. I can write in public, and I can write in private. I'm pretty good at concentrating on what I am doing. I don't want to be seen writing; I don't go to Starbucks. It’s more that I like the work, and it's a pleasure to get lost in it. That can happen anywhere.

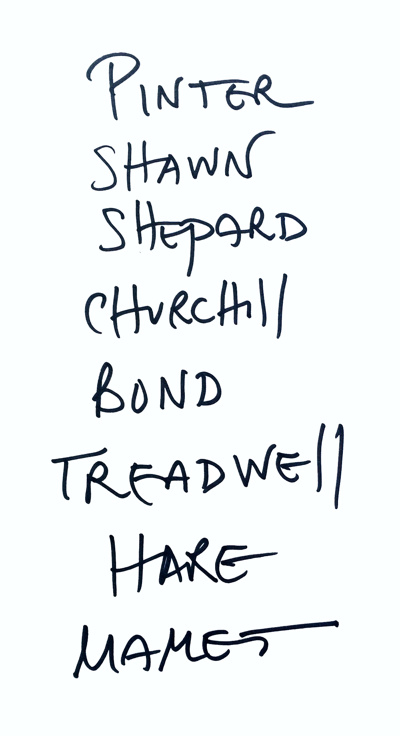

What writers inspire you?

Describe your process.

Now living more here in New York than anywhere else, the process has been a great one. I'll break a day down into sections; I'm essentially like an untrained puppy. If you write in the morning and get those five pages done, then you can have breakfast. Then you can write some more, and you get a walk in the park. Come back write another five pages. Hey, what about a matinee today? Let's go down to Film Forum and see what's playing. Come back write some more. In that way, I've ended up writing up to 25 pages a day. You can get into a place where two pages can be labor because they’re just not coming. Not every day is as whimsical as that one I described. But that's a good day with many treats and lots of writing.

So you’re treat-driven?

I think you should reward yourself. I think it is work. I came from a very blue collar family and though no one disdained what I wanted to do, there was a general sense of “That's not really work. Let's not kid ourselves—Dad's a truck driver, we work on a farm here, that's actual work.” I've always approached it with the same ethic that I had to clean a barn or whatever it was: You pitch in and roll up your sleeves and get the work done. People will say, “You're very prolific—how do you write so much?” I'm like, by writing it. It's weird how things stack up.

Do you think there is such a thing as a LaButian character? If so, how would you describe it?

I think they're flawed, obviously. I've made a career writing about flawed people. They are people who are sometimes well-meaning, and sometimes not. Mistakenly people sometimes think they are sociopathic, psychotic, misogynistic, misanthropic and outside the parameters of the continuum, but rarely have the characters been that to me. They're just people who make terrible mistakes, or they're cowards or braggarts. They are often men characterized by a desire to do better and be better than they are. Sometimes they stumble and sometimes they get to their feet. Sometimes they don't, and they drag people down with them. I think they are people who are essentially very human—but that means to me flawed, troubled, funny and having the best intentions even if they're casually brutal to each other.

What play changed your life?

What are the biggest misconceptions that people have about your work?

Well, that the work speaks for me certainly. That's an easy mistake to make with any author. You assign—always the worst qualities, no one ever picks the greatest character you've written—and think, "That must be you." You were capable of thinking that awful thought, so that must be you. You must be riddled with bad shit inside. No, you just have to be able to think on both sides of the wall. I think that's a big misconception of me. Also, I'm not writing fantastical people in the science fiction world—a lot of it are very human relationships. So a lot of people think that these are thinly veiled stories of my fears or desires. I'm really just trying to tell a story and trying to find another group of people to write about. I think there’s also the whole misogynist thing—that I'm really hard on female characters. I think I actually write pretty good female characters and am harder on men than on women. But that gets turned around often. It got labeled early, so it's hard to shake sometimes. It's not that I've embraced it, but I’ve just continued on in spite of it. Sometimes the work reinforces that; sometimes it's contrary to that.

What would you say you're most obsessed with as a writer?

I don't really write thematically, but I certainly think that for as much as people will deny it, I've written again and again about love: About relationships, about people who are in love and relationships that defy the usual, the norms and it's the parameter. How far can that word stretch? One of the central conceits in both of [Wrecks and All the Ways to Say I Love You] is can a person really love another person if they've lied to that person for almost the entire course of their relationship? It's not quite the same in both pieces, but there is an element of that question about truth and lies. Some people would say no flat out—if you're lying to a person, do you then love them? I'm not so sure. I don't think it's my duty to know. I think I'm supposed to raise the question.

What is the hard part of being a playwright that no one ever told you?

I think it’s the kind of self-starting where you never give up. When you really get down to it, it’s as simple as putting pen to paper; you sit down and write. When I was teaching, I stumbled on a great quote. Maxim Gorky wrote a letter to Chekhov to ask sort of the same thing that students ask all the time: What's the secret? The answer is there's no secret. He sent back to him three words. "Write, write, write." It's as simple as that. He didn't write tons of plays either, but he wrote hundreds of short stories for a man who only lived until his early forties. He wrote a lot, and I don't think he discovered a genie. That's the only thing I've discovered—and also the isolation of it. It really can be an isolating career. You will spend a lot of time on your own. I do think that because of that, you should then embrace the idea of collaboration and rewriting. So many people seem to dislike the idea of rewriting. I've never understood what that was. I'm happy to tinker after the thing is done. It is part of the process to me.

What is something that aspiring writers should do or see?

They should read. That's where I started. Just read everybody else. See what everybody else is doing. Don't be jealous, though, of course, you will be. When you find one that make you say, “God, I wish I would have written that.” That's what you should read over and over. If they're around theater, they should go all the time. They should do their own stuff—stage their own work. That was the thing for me. The first movie I did myself. It's always back to that roll-up-your-sleeves-and-get-it-done mentality. There are so many places that you can get material out to people who are willing to watch, and there are so many different kinds of mediums now. If you narrow your audience and say, “I'm not really a writer until I'm on Broadway”—well, you've narrowed your possibilities of what will make you satisfied down to about 15 theaters. Multi-million dollar productions are great, but I'm not going to let that be the guide for me. I couldn't be happier being in this theater [the Lucille Lortel]. People have to get out there and make things happen for themselves. I think it's important.

What's your favorite line in All the Ways to Say I Love You?